Similar to the custom of decorating wells and fountains (Osterbrunnen), the tradition of Osterwasser (Easter water) is (or was) not a typical German Easter custom but a regional one. Easter water is water collected on Easter Sunday before sunrise and has special powers.

The custom of collecting water on Easter morning dates back to pre-Christian times when Easter wasn’t Easter but a pagan spring celebration. Over time it has been overlayed with Christian motifs and some superstitions around the water are clearly derived from Christianity.

For example, it is said that water fetched between 11pm and midnight on Karsamstag would turn to wine, the water could cleanse from sins, or purify the soul. In some parishes, Easter water was used as baptismal water throughout the year. In others, the water for baptisms was just called Osterwasser because it was blessed on Easter.

Where is Osterwasser a custom?

Usually it is said that the custom of collecting water early on Easter Sunday could be found in different regions, among them Upper Franconia, Pomerania, and Saxony. It was practiced by the Sorbs, a Slavic minority in the Spreewald region in Saxony, until the 1950s. Nowadays, it’s only some villages who still observe this custom.

However, after researching a little more, I have come across different sources, from Berlin (1821), from Hamburg (1879), and from Lower Saxony (1936), where Osterwasser is mentioned. Maybe the custom of collecting Osterwasser was more widespread than we thought.

The first source from Hamburg is “Mitteilungen des Vereins für Hamburgische Geschichte“, No 3, Januar 1879, p. 31. In these notices, the author F. Voigt writes that the belief in the healing powers of the Osterwasser has disappeared, implying that it used to be practiced in the area. He continues to tell the story of a woman from Hamburg who was upset with her neighbor, whom she had been fighting with, because he spoke to her when she was walking home with Easter water rendering the water without any blessing and power.

The second source is “Osterwasser in Niedersachsen” written by Helmuth Plath in “Die Kunde” (4.1936). Plath’s survey covers areas, the north (Winser Elbmarsch), the Lüneburg Heath, the Oberweser in the south, and the Harz mountains in the south-east. While there are variations, the custom itself was never questioned.

What is Osterwasser?

Osterwasser or Easter water is water collected on Easter morning from a river, well, or spring before sunrise. It has healing and protective powers and won’t go bad. That is the part that all legends around the Easter water have in common. The details vary from region to region or even town to town.

Most often it was (unmarried) women and girls going to collect water, sometimes it was the mothers, sometimes children, some were dressed in good but everyday clothes, some Sorbian girls wore their traditional Tracht.

Usually, no word should be spoken when the water is scooped and carried back (unberufen, unbeschrien – unbidden), sometimes you shouldn’t even be seen; we still have similar superstitions that you shouldn’t say your wishes out loud – when tossing a coin into a fountain or blowing out your birthday candles – otherwise those wishes won’t come true, or in case of the Osterwasser it would turn back into normal water or Plapperwasser. Often, young men would try to startle and tease the women to get them to speak or laugh.

In the early 19th century in Berlin, the teasing had gotten out of hand that the police kept the men away from the women who were collecting water from the Spree river.

But there are also accounts that the people (mostly young men) in charge of the farm animals would fetch the water.

Dürft nicht auf der Männer Spottrede hören!

Wandelt lautlos zum Flusse, neiget euch hin

Und schöpfet das Wasser mit gläubigem Sinn.

Sonst erfüllt sich kein Zauber, sonst fehlt heil'ge Kraft,

Die Schönheit euch bringt und Gesundheit schafft.

Zieht schweigend heim, was auch trifft euer Ohr,

Ehe die Ostersonne rauscht flammend empor!

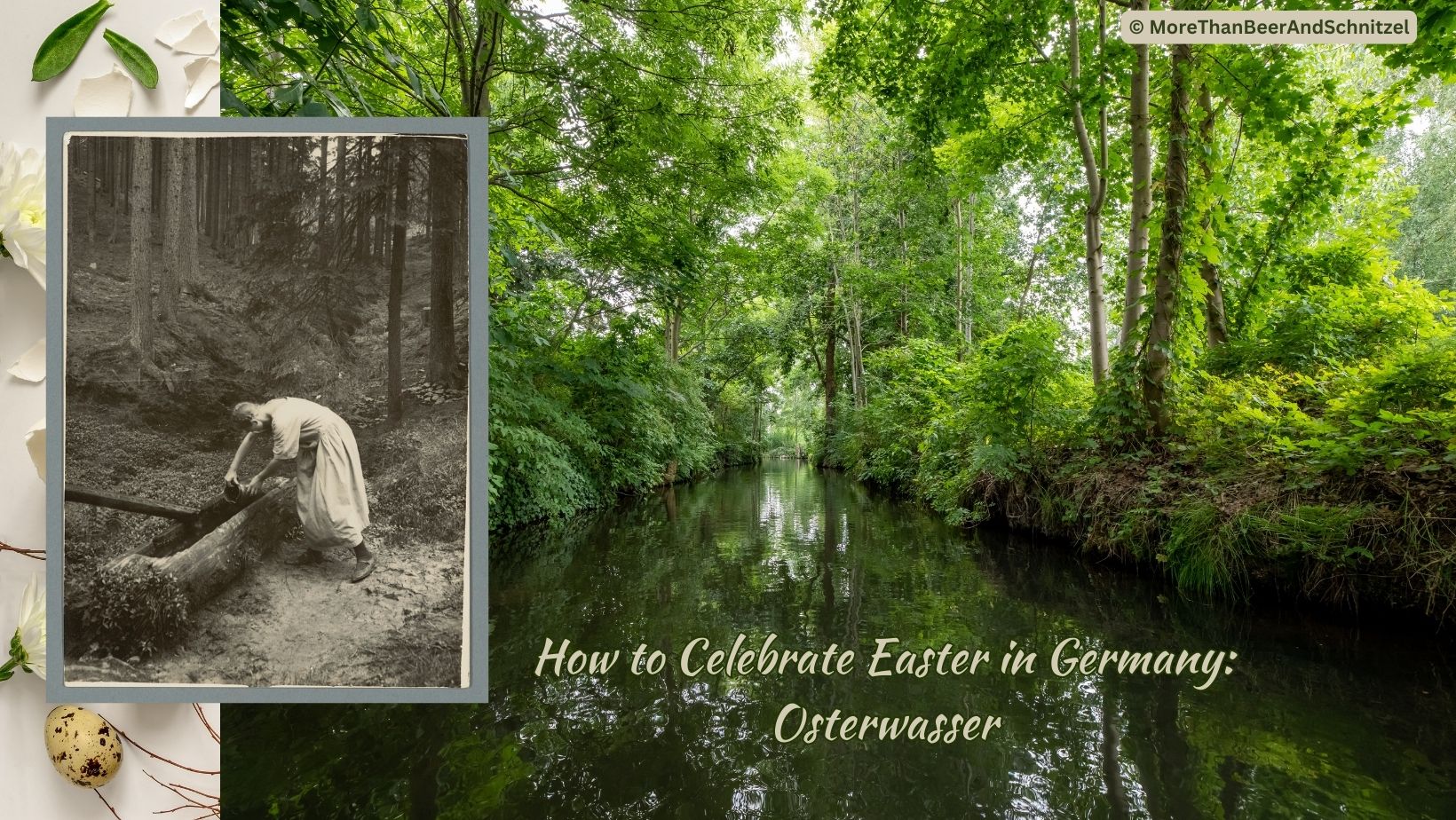

The postcard belongs to the series “Thüringer Sitten und Bräuche” published by Friedrich Martins Kunstverlag, Erfurt. The cancellation date on the stamp is April 6, 1901.

The poem addresses the girls on their way to the river to scoop water. It warns them not to listen to anything the men might say to them, but to stay silent and collect the water faithfully. Otherwise there will be no magic, no blessed power that brings beauty and health. It ends with a final warning to carry the water home, not listening to anything, before the Easter sun rises.

Alternatively, the custom in the Harz mountains (as published in Leipzig in 1867) requires to scoop water against the current and also say the following phrase: “Hier schöpf’ ich Christi Blut, das ist für siebensiebzigerlei Fieber gut.” (Here I scoop the blood of Christ which is good for seventy-seven kinds of fever.) Here we see the Christian influence on the pagan tradition.

das ist für siebensiebzigerlei Fieber gut.

There is also variation as to when the water should be fetched. Between 11pm and midnight on Karsamstag (Saturday before Easter), or after midnight, or early in the morning of Easter Sunday before the sun rises.

Other differences concern the source of the water. In most areas it has be flowing water, in the Harz region it is specified as water flowing from west to east. Sometimes, the water has to be fetched against the current, sometimes with the current, often it doesn’t matter. In other regions, water collected from a well or a pond is also an acceptable source for Osterwasser.

What is special about Osterwasser?

Healing and protective properties

Osterwasser had special healing and protective powers. It was good for your skin and protected from sickness. Drinking the water helps against fever and it supposedly helped especially for eye conditions. Read here the account of Margit Vogel who as a child always had swollen and crusty eyes when waking up. Her eyes cleared up after treatment with Osterwasser which was fetched by her mother and grandfather from a river miles away.

People washed themselves in the water; especially young women hoped to stay beautiful for the entire year by washing their face and neck with the water. Recently married women hoped that drinking the water would help them get pregnant. But in other areas, women and men alike washed themselves with the Easter water for a happy and healthy year.

Sometimes cattle was led to the river early in the morning to be washed. Alternatively, the animals could be sprinkled with the Easter water. In some areas, the farm animals were watered with the Osterwasser in order to recover from any sickness or to prosper.

Staying fresh

It is said that Osterwasser won’t go bad but will stay fresh. That way people had the healing water at their disposal for the coming year. The Osterwasser was usually kept in an earthen jug in the cellar.

Interestingly, as early as 1796 the notion that Easter water wouldn’t go bad had been discredited and labeled superstitious. In a eight page explanation in “Nützliche Sachen für den lieben Bürgers- und Bauersmann um Betrüger zu entlarven, Geld zu sparen und Verbesserungen von mancherlei Art anzubringen” (Useful things for the good citizen and farmer to expose crooks, to save money and to apply improvements of all kinds), the author shows that there is nothing special about water collected on Easter morning before sunrise. If the water stays fresh longer than other water it is because special care is taken. Any water that is filled in a jug to the top and is properly sealed will not go bad as quickly as water that is kept open and exposed.

Helping in matters of the heart and telling the future

Some accounts from the Lüneburg Heath claim that the water can be used as a love potion to make your loved one stay true to you. You may also sprinkle the man you want to marry with the water to help things along.

Should two people be in unlucky in love, they should drink three spoons full of the water and say “Untergeh’n, aufersteh’n, immer treu, ewig neu” (To go down/to sink, to resurge, always loyal/true, forever new).

The Easter water was also used to predict the future. You take a thimble (though I feel a typical thimble might be too small, but the word Plath uses is Fingerhut) and add ashes, bread, a barley grain, and Osterwasser. The thimble is then put over a fire. When the ashes rise before the water is boiling, somebody will die. Should the bread come up first, somebody in the family will get married, and when the barley rises first, it will be a good harvest.

Sources and Resources

- Wiki Osterwasser -dt

- Wanderer: Deutsches Sprichwörter-Lexikon

- Osterwasser im Spreewald

- FAZ -Sorbische Osterbräuche

- Deutsche Digitale Bibliothek

- Historische Bildpostkarten Universität Osnabrück

- SLUB: Sächsische Landesbibliothek – Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek Dresden

- Osterbrauchtum in Pommern

- Sachsen-Anhalt Journal

- Johann Wilhelm David Korth: Neuestes topographisch-statistisches Gemälde von Berlin und dessen Umgebungen (1821)

- Christian Gottfried Voigt: Gemeinnützige Abhandlungen, Weidmannische Buchhandlung, Leipzig, 1792.

Only registered users can comment.

Comments are closed.